“Christian Nicolas grew up in a home where reverence for photography, literature, and the arts were evident. Molded by two parents professionally involved in photography, Christian was drawn behind the lens. Under the guidance of his parents and Uncles, Christian tested, learned, and entered the world of picture taking. By the age of twelve, he was already experimenting with special effects using the darkroom of his parents’ lab to create abstract work. Christian’s high regards for his father inclined him to benefit from the commitment he displayed teaching and writing. These particular surroundings shaped his personal interests and deepened his appreciation for the arts in general.”

Katia: How did the name Kristo Art come about?

Kristo: My birth name is Christian Nicolas. Tiga was the one who advised me to find a way to disassociate myself from the artist within. When Kristo Art works, Christian Nicolas completely disappears. Tiga was the one who actually gave me that name. I carry it in his honor.

Katia: When you sign your work, do you use Kristo or Christian?

Kristo: I sign as Kristo.

Katia: Tell me about Master Tiga.

Kristo: Tiga was actually my father-in-law. During the last two years of his life, he was mostly in the hospital battling cancer. I recall when he came to do a show in Fort Lauderdale once, he handed a canvas and told me to do something. I told him I didn’t know how to paint; he ignored my response. Tiga believed everyone had an artist somewhere inside of them. I took the canvas he gave me and attempted to “do something.” I don’t remember what I did, but Tiga didn’t judge. He simply gave me another canvas, and said “Try again.” I tried again. Tiga kept giving canvas after canvas, telling to let the artist in me take over. Let whatever that was inside come out onto the canvas. I think finally I did.

Katia: What was Tiga’s greatest gift to you?

Kristo: Tiga gave me more than one thing. My approach to art is one. More importantly, he helped me to understand that when you [the artist] are ‘present’ or when the mind is ‘thinking,’ then the art becomes automatic, not authentic. It is not coming from a deep enough place. You think you might be creating, but you’re just going through the motions. There are two kinds of artists: commercial and the artist whose soul speaks through the art. There’s what’s going on outside of you and what is happening inside. Sometimes the line blurs between the two. Tiga taught me to focus on what is happening inside. Once a piece comes out of me, I apply the techniques learned from Tiga. Sometimes I can look at a canvas with colors applied to it and not know for days what it is or how to interpret it. Because, for me, true art creates itself.

Katia: What would you say is Tiga’s legacy to Haitian art as a whole?

Kristo: Haitian art took a real turn with Tiga. Before that, other Haitian masters were influenced by Europeans. When Tiga came, he began a new movement. He took a bunch of farmers and peasants and gave them the freedom to express themselves artistically. He educated those people through art by allowing their souls to speak in whatever form they chose: painting, music, pottery-making, whatever.

Katia: You write in Beyond Words – Beyond Colors that you disappear into the canvas and sometimes it take days before you can even recognize what it is you’ve created. Was disappearing into the canvas something you had to learn over time, or was it always that way?

Kristo: I think Tiga taught me that. He was never one to impose his method on you. He just let your art come through. I am like a conduit—a vehicle for the thing inside trying to make itself manifest. When most kids were in the streets playing games, I was at the library escaping into books. This is probably why it became easy for me to let myself transform into a blank slate. I become like a sheet of paper—a carte blanche for whatever needs to come through me. It’s sort of like being possessed. When I work, a bomb could be exploding just outside my window, and I would never know.

Katia: Have you every attempted to resist transforming into a blank slate?

Kristo: No. Not at all. Actually I do my best to let it flow and nurture it. Because I know if I don’t, the work will suffer. It’s like the laws of the universe . . . It’s like a sort of radio station. If you want to hear a certain music, you have to tune to that station. If not, you end up listening to something else. It’s like a current flowing to me.

Katia: Were you always good, or did your genius develop over time?

Kristo: Every artist develops over time. When you experiment you become better. I guess it’s like everything else.

Katia: If you could not paint, photograph, or write, what would you do?

Kristo: Oh God, I don’t think I would be a living being. When I was 3 years old I remember wanting to become a doctor. I wanted to take care of my mother and my godmother. I wanted to know how the body works. But I come from a family of artists. Photography and literature dominated our lives. My mom and dad made a living out of it. When people were traveling, they came to my parents for their passport pictures. By the time I was nine years old, I had a camera in my hand. It started then. But photography can be mechanical. You don’t have to be inspired to snap pictures. Painting and writing are different. Nothing mechanical about those.

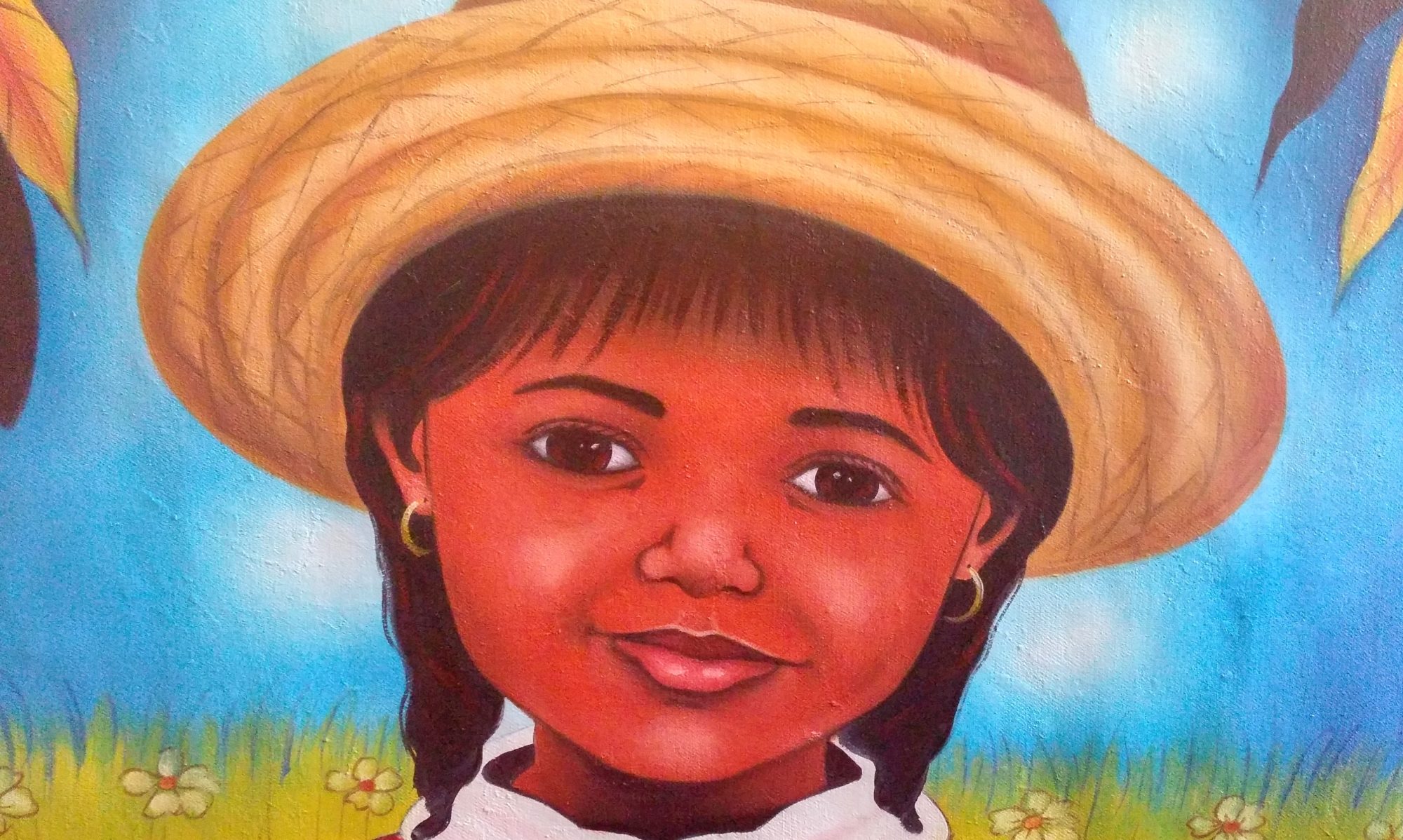

![Agoueth_Aroyo_40_x_40_$4000[1]](http://www.voicesfromhaiti.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/Agoueth_Aroyo_40_x_40_40001-300x300.jpg)

Kristo: Totally alone. I want no interference or the outcome will not be that good. In a sense, it would be contaminated.

Katia: When you create, do you need to do so in complete silence?

Kristo: Complete silence. I have two daughters and a son. I am very proud of them. Very proud of them. But when I am painting, I need complete silence.

Katia: What do your children think about your work? Are you a famous artist or just daddy?

Kristo: My children love my work. But I’m just daddy. Actually, maybe I’m a combination of both.

Katia: Do you ever give your children some of your work as gifts?

Kristo: Not yet. I think they are too young to appreciate it. They know if they want a piece of my art, all they have to do is ask me and I’ll give. But I don’t trust them to take good care of it. They are interested, but not to the appreciation point that I want them to be.

Katia: What pleases you most when people view your work?

Kristo: When people can actually communicate with the work. When they see things that aren’t visible to the naked eye. I just came back from Italy two days ago. The organization that invited me donated its proceeds to fighting child pornography and abuse in Italy. I think they understand my work. They understand that it’s something more than just pictures. They know I’m trying to do something more. That means a lot to me.

Katia: When you’re not being a conduit for the art, what does Kristo like to do?

Kristo: I’m always working. Right now, I’m working on my thrid book “Au dela des mots et des couleurs” a french book of poetry and art. I am always working on something.

Katia: Is it true that you’re planning to return to Haiti to live?

Kristo: Yes, it’s true. I’m at a certain point in my life where I want to be back in Haiti. I’ve done all I could have done here in the States. When I think of Haiti today, I want to cry. But I remember a Haiti that was beautiful. Sure there were bad things going on, but I was pretty much a happy child. If you had one gourde you could eat. If you had five gourdes, you had a ton of money. Nowadays, ten gourdes won’t even get you a small meal.

Katia: What will you do in Haiti beside paint?

Kristo: I work with an organization that takes care of 500 kids. The founders have built a school in Mirabelais. The kids range from 6 to 12 years. They feed the kids at least one meal a day. It’s important to care for people who cannot care for themselves.

Katia: Why do you want to move to Haiti especially at this time?

Kristo: It’s a time for reconstruction. Rebuilding. And also I’m thinking about my own personal life—how I want to retire; the kind of life I want. I’ve lived a complicated live. I don’t want that anymore.

Katia: You’ve traveled quite a bit. What is your favorite spot in the world?

Kristo: Haiti. I love the mountains. If I could have a little chalet in the mountains, wake up every day and watch the sunrise. That would be a great living. I love Haiti.

Katia: In your opinion, what is happening to Haitian art today?

Kristo: Is there real art in Haiti today? Can’t say. It’s mostly copies of copies. The inspiration and risk-taking are not there anymore. In addition, the artists are mostly living abroad. They’re not in Haiti anymore. And for the most part, we’re all struggling because the copies are so readily available. Any artist will tell you the same story. The fact remains, however, that Haitian are artists at heart. Every person you talk to is either an artist or has one in the family. We are all artists. Struggling artist.

Katia: Who are the masters of Haitian today?

Kristo: We have many commercial artists today. A master is somebody like Tiga. He was a sort of everyman. He was a teacher. He inspired you. He even co-founded the Saint-Soleil Rotation Artistique with Maud Robard that began the post-naïve method that encouraged farmers to freely create. They gave them materials such as canvases, paint, clay, writing utensils, etc. That method was applied in many parts of the world. France’s André Malraux wrote about it in his book. Tiga was praised by critics worldwide. I don’t want to name any names, but today all it takes is the right contact for Haitian art to sell. The form has been exploited, distorted. Copiers are copying the copiers. It’s a mess.

Katia: Whose art work do you display at home?

Kristo. Tiga. And one or two pieces of my own.

Katia: What advice would you give to upcoming artists?

Kristo: First get a job to pay the bills. It’s hard, but when you have to express yourself through art. It’s hard to stop.

Katia: What is the number one rule Kristo lives by?

Kristo: Honesty. That’s my main thing. I thank my parents for teaching me that. I hate liars. Whatever your truth is, just tell it and deal with the consequences. Be yourself. Don’t try to please anybody by pretending to be someone else. Just be yourself.

For information about Kristo Art’s amazing work, visit www.kristoart.com

J’apprends à te connaître… 🙂