I heard Marilène Phipps Kettlewell read from her book, Crossroads and Unholy Water (University of Illinois Press) many years ago at the National Museum of Women in the Arts. Two words stayed with me: “Man Nini.” The tenderness and passion with which the artist, poet, and short-story writer had spoken them made it clear that she was/is a woman who loves deeply or not at all. I wanted to ask her many questions. I wanted to understand the Haïti in her heart. I am thankful she took the time to answer my many (many) questions here for this exclusive VoicesfromHaiti INNERview. -Katia D. Ulysse

I heard Marilène Phipps Kettlewell read from her book, Crossroads and Unholy Water (University of Illinois Press) many years ago at the National Museum of Women in the Arts. Two words stayed with me: “Man Nini.” The tenderness and passion with which the artist, poet, and short-story writer had spoken them made it clear that she was/is a woman who loves deeply or not at all. I wanted to ask her many questions. I wanted to understand the Haïti in her heart. I am thankful she took the time to answer my many (many) questions here for this exclusive VoicesfromHaiti INNERview. -Katia D. Ulysse

Everyone has his or her own private Haïti. How would you describe yours?

My Haïti is torn and unsettled, haunted by memories of a paradise I could never see or inhabit again, because it either never existed but in my inner being’s sensibility, or it is gone for good. Life is movement. To hope for things to remain the same is to hope for death.

What emotions—if any—do you experience when you see the word “Haïti” suddenly, say at a supermarket or a department store?

When I see the word Haïti, I am not at peace—unsettled emotions are stirred—a disquiet with what was, with how the country itself, as well as how class and racial relations have evolved (or not evolved), regardless of the earthquake, and in spite of the earthquake. Being hopeful is an effort. I keep making that effort.

I am not at peace with my personal relationship with Haïti either—being far, separated, ripped apart, and not having done enough—whatever other people point to in what I have done, or contributed to my country, never feels enough—whether it is representing Haïti abroad with pride; fighting negative stereotypes in my painting and written work, public lectures and poetry readings; keeping alive an awareness of the power and uniqueness of its cultural, spiritual and physical beauty; inspiring compassion for the ongoing vulnerability and struggles of its people, and the never-ending abuse they suffer from the political and economic world, equally at home and from foreign powers that have never ceased to compete over the ownership and free use of it ever since colonial time.

Time and again, I dream of the life I could have had in Haïti had I never left, the sense of belonging I would enjoy. Yet, I am keenly aware that all that I have become (and what inspires you to interview me here in the first place), would never have been. It would have been other, and perhaps just as good, humanly, professionally or spiritually speaking, but I have come to value, and not regret, what I have done with my life so far. The seemingly wrong choices and the ensuing sorrows have been worth it. There is an intelligence at work in the universe, and in each of our lives, that knows what is being done, and why—the significance of every step of our lives eventually becomes apparent. My regret, and my cross, is that the purpose of my life required that I leave home in order to find and manifest it.

Do people think you are Haitian upon first meetings?

No, they do not—in the average American or European, Haïti is associated with a black population. But I get the same reaction from Haitians, and even if I speak kreyòl to them—they remark on my mastery of their language, and wonder where, and why, I have learnt it. What they see in me is a “white woman.”

I can’t help wonder how Haitian writers like the late Jacques Roumain (Gouverneurs de la Rosée—Masters of the Dew), the late Marie Chauvet (Amour, Colère, Folie—Love, Anger, Madness), the late Jean Dominique (Radio-Haiti-Inter), Lilas Desquiron (Les Chemins de Loko Miroir—Reflections of Loko Miwa), or even the Haitian painter, the late Bernard Wah, of Chinese descent—how they have dealt with that raw question—all the racial issues of appurtenance, belonging or rejection it alludes to. All of them belong to the Haitian controversial mulatto class. All of them hold high the flag of Haitian arts and culture, in Haïti and abroad.

The fact that this question of skin color, the reaction I may get from its pale shade, abroad and at home, is the second question of this long interview, shows how raw this issue still is, that peace and full brotherhood among Haitians under a same flag, have still to be reached. But this is unfortunately not unique to Haïti. The ways human beings find to marginalize each other, and maintain boundaries of power and status, is a sad human fact.

The irony is that I am as Haitian as any black Haitian. One must consider that Caribbean cultures are cultures of contact, born of the contact, and clash, of races, and that the true Caribbean (therefore the true Haitian), may be said to be a mixture.

My family was in Haïti from the very beginning of its history after the slave revolution of 1804—my ancestor, James Phipps, an Englishman, was among the first foreigners to be naturalized Haitian by Jean-Jacques Dessalines himself in 1805.

Thereafter, every generation of Phipps has given birth to at least one man involved in Haïti’s government and politics, often in coup d’états. They were also involved in education and religion—on my grandmother de Lespinasse’s side, my ancestors were among the founders of the Petit Séminaire, College St. Martial; recently I was in front of the ruins of the church Saint Louis Roi de France, at the bottom of Turgeau, which my family had built, and where my father’s funeral mass was held.

My great grandfather, Edmond de Lespinasse, was a powerful lawyer in his days, a man of letters, and a famed orator—Port-au-Prince closed down all businesses when he was due to plead in court—everyone wanted to go listen—it was great theatre. He also was Haïti’s ambassador to Paris; I remember finding one of his cards in my adolescence and reading with emotion, “Edmond de Lespinasse, Envoyé Extraordinaire et Ministre Plénipotentiaire de l’Ambassade d’Haïti à Paris.”

What reaction do you usually receive when you inform folks that you are Haitian?

What reaction do you usually receive when you inform folks that you are Haitian?

From non-Haitians, I get surprise. From Haitians, most often I get disbelief; and all too often unease follows the disbelief—class awareness, deduced only because of my skin color, quickly seeps in, and creates distance. Many Haitian people, without knowing a thing about me—my professional strivings, my emotional, socio-political, or spiritual foundations—react to what my skin color represents to them, and not to who I am. In this way, they rob me of my greater humanity. They unwittingly reinforce the enduring solitude in being a Haitian away from home.

Of course, much of this discomfort depends on who my interlocutor is, what his or her own internal Haïti is, and what experience of the Haitian mulatto class he or she has. On the whole, I have found that the Haitian who has grown up in the U.S. from an early age, or from adolescence even, is much more free of these social impediments to spontaneous human interaction.

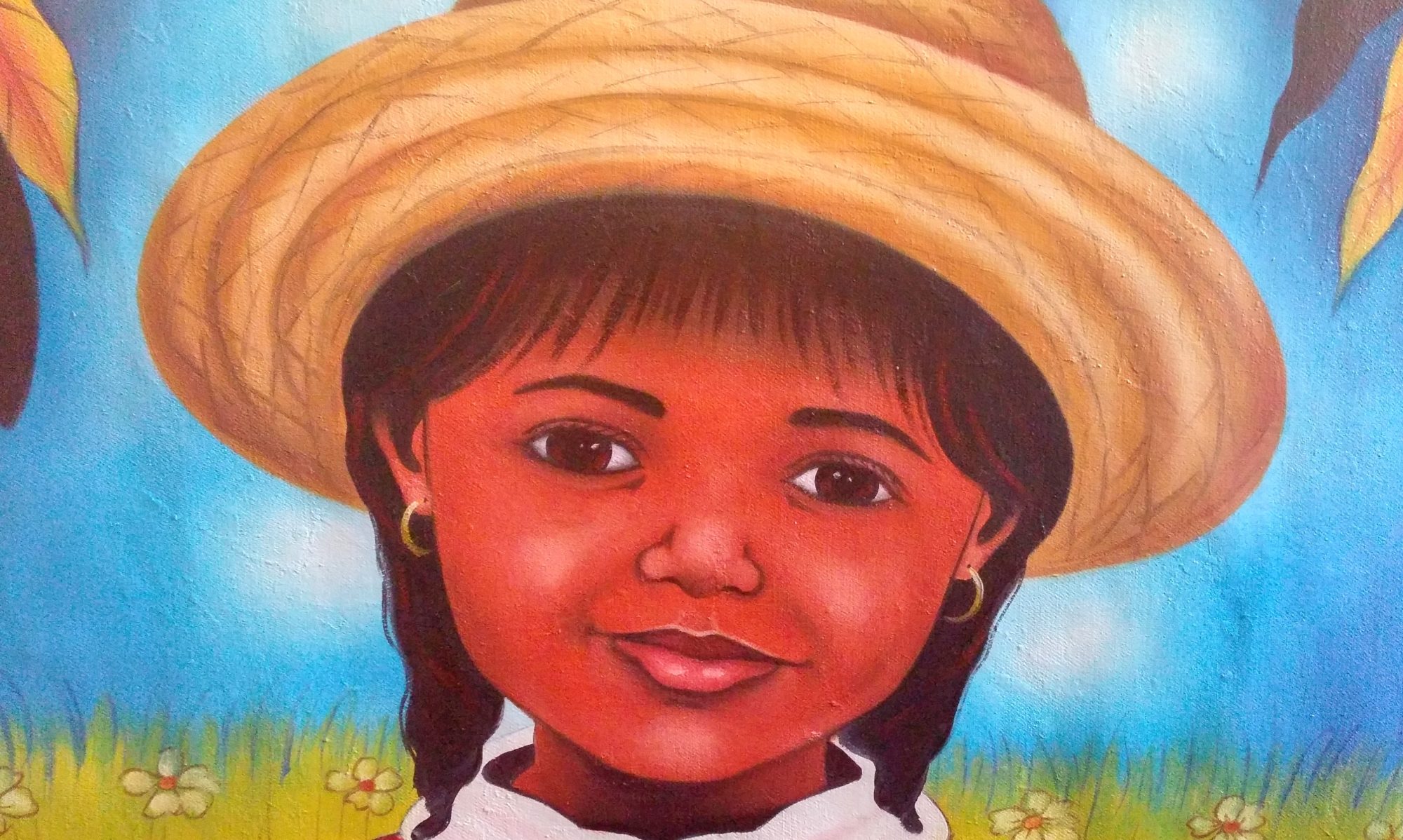

I had a wonderful experience in the Fall of 2011, teaching poetry writing, in Kreyòl, to three classes of Haitian children at the Kenney School, in Boston’s Dorchester neighborhood. Their jaws dropped when they first saw me enter the class when they expected a new Haitian poetry teacher. But they cheered me afterwards, and each time I came into the classroom. “Bonjou timoun, kouman nou ye?” “Byen Madam!” I soon had them write poetry they never imagined they would; I had them dance freely, repeating after me this sentence from a poem I wrote for them, “Madi Gra, m pa pè w, se moun ou ye!—masked man, I am not afraid of you, you are human!”

Marilène Phipps Kettlewell on her childhood

At the Maternity Bourand, in Port-au-Prince. I think that it was in the Petit Four area. Docteur Bayardel delivered me (or my mother…)

How would you characterize the overall experience: good or bad?

If you mean my birth, then the answer is “bad”—I was pulled out of my mother with forceps—I weighed 10 pounds, was jaundiced, and bald. I ripped my mother apart two days before Christmas. This is what I mean about Docteur Bayardel having “delivered” my mother rather than me.

If your question is rather about my childhood, I would say the experience was idyllic, and even if family dynamics had problems that scarred me. And if you consider the privileges in which I was born, I would be cruelly ungrateful to say that my childhood was not good—I was loved, I had access to education, dream-play, and to all possible material goods a child could ever need.

But life is a rite of passage—nobody escapes suffering, beginning with, or in, childhood, and no matter what level of the social ladder out of which you initially spring.

Is there someone—relative, family friend, housekeeper—who holds a special place in your mind and heart?

All my relatives touched me deeply and in various way, beginning with mother, father, aunts and uncles—they were the gods of my Mount Olympus.

My cousins and my brother were equals as siblings in my heart, even if very different from each other in personalities, and in the ways they affected or touched me, or cared to touch me.

But my cousin, and godfather, Guslé Villedrouin, of the group Jeune Haïti that tried to overthrow Papa Doc, may be the one who comes to mind first, as one who holds a special place, not only because he was a lovely being—a romantic, a generous heart, a handsome devil—who at 23 was willing to give his life for his countrymen, and did, but also because his death and beheading scarred all of us in the family forever.

His death was a difficult gift, but a gift nonetheless. I wrote about him in the story Dame Marie that is part of my Iowa Prize winning collection, The Company of Heaven: Stories from Haiti. I am not done thinking, or writing about him either. Or about anyone—I ruminate like an old cow, I chew things over and over, until I have assimilated the food completely.

Housekeepers, cooks and gardeners were, and still are, part of my emotional family. I wrote about Man Nini, Auxilia, Gracilia, Dieudonne, Saint Ayus, Aramis, Venant, and many others, both in my short stories, and in my collection of poems Crossroads and Unholy Water, published by the University of Southern Illinois Press. And in my writings of today, yet unpublished, these charmers of my life still find themselves woven in my stories or memoirs.

Why did they matter then. Why do they matter now?

They matter now for the same reasons they mattered then—they provided love, poetry, texture, imagination, and kindness to my life, unwittingly.

And because I felt love for them in return, they challenged me deeply—causing me to reflect on, and try to make sense of the differences between them and me—their fate in comparison to mine—they forced me to discover and articulate social concepts I would only learn about much later in life; they taught me pain because I felt for them, suffered for them, I learnt to miss people through them. I am indebted to them for the sufferings they endured that allowed my heart to be enlarged.

What is the worst memory of your childhood?

The death of Guslé Villedrouin and the public execution of his friends Marcel Numa and Louis Drouin in front of the Port-au-Prince cemetery, which was televised, and broadcast live. I was in Haïti at the time. I watched it all, over and over, as that broadcast was repeated for a week’s time, if I recall correctly.

Do you have children of your own now?

I have not given birth to a child. My destiny had it that I should raise other people’s children—stepchildren or other. It’s been good and bad. I am told that there is a sentence in the Bible that more or less says, “Blessed the woman with children; blessed the woman without.” My blood line stops with me.

I have had to evaluate, and make peace with the relativity of blood connections between human beings, and see that love is what really connects us—children have been seen to be cruel to their parents, while we fall in love with strangers, give our lives to them in marriage, or for them in instances of sacrifice. I have had to enlarge my heart, widen my sense of family, understand that we all raise each other, we all are children and parents of each other. I therefore have countless children.

If you could change Haiti’s over-all landscape, where would you begin?

Erase poverty—hunger, homelessness, lack of medical care. Establish free education for all; better educational and language reforms; medical reforms matched by the development of modern hospitals that can provide free and proper care to our population, and distance us progressively from an unhealthy dependency on international aid; urbanization reforms at many levels, and whereby slums are destroyed, replaced by decent, government housing for the poor; reforestation, agricultural reforms, land reforms; civil protection by a reliable Haitian army; wide ranging Culture and Arts programs that benefit all ages and all levels of the population, as well as support a tourism industry etc… where do you stop?

How do you imagine Haiti will look like in 20 years?

A land of beauty, freedom, justice, and equality.