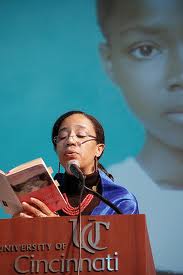

VoicesfromHaiti: For those of us who are not familiar with your work, tell us what you do and who Myriam Chancy is.

Myriam Chancy: I am a writer/scholar and professor of English (American/Caribbean) literature.

Myriam Chancy: I am a writer/scholar and professor of English (American/Caribbean) literature.

After obtaining a BA in English/Philosophy (4-YR ADV, with Honors), from the University of Manitoba (1989) and my MA in English Literature from Dalhousie University(1990), I completed my Ph. D. in English at the University of Iowa(1994).

VoicesfromHaiti: Who or what inspired you to push forward with your studies?

Myriam Chancy: I was inspired to obtain my MA and Ph. D. primarily because I realized early on that I had received next to no education regarding people of African descent, and I thought that continuing forward would allow me to find that information.

I started out focusing on African American literature then realized at the dissertation stage that I could do the same in Caribbean literature.

VoicesfromHaiti: How long after obtaining you Ph.D. were you awarded tenure?

Myriam Chancy: In 1997, three years after obtaining my Ph. D., I was awarded early tenure on the basis of two influential books of literary criticism published in the same calendar year, Framing Silence: Revolutionary Novels by Haitian Women (Rutgers UP, 1997) and Searching for Safe Spaces : Afro-Caribbean Women Writers in Exile (Temple UP, 1997). I am probably most pleased with this achievement, the early tenure, and the publication of Framing Silence since FS was instrumental in creating a viable space for the study of Haitian women and Haitian women’s literature in literary studies.

Searching for Safe Spaces also won an OAB award from Choices, the journal of the American Library Association in 1998. I was also one of two founding editors for the Ford-funded academic/arts journal, Meridians: feminism, race, transnationalism, housed at Smith College(2002-2004), which was recognized with the Phoenix Award for Editorial Achievement in 2004 by the Council of Editors of Learned Journals (CELJ).

VoicesfromHaiti: You also write fiction. Why specifically did you choose that forum in addition to all the academic work you do?

VoicesfromHaiti: You also write fiction. Why specifically did you choose that forum in addition to all the academic work you do?

Myriam Chancy: As a creative writer, I’ve been interested in the novel form as a forum for the expression of contemporary realities since the mid-1990s. As a novelist, I have focused to date on themes of history, class, gender, spirituality /mysticism and sexuality in the context of Haitian culture both in Haiti and its diasporas. I’m explicitly interested in re-working the novel form as a means to express complex subject identities specific to Haiti.

VoicesfromHaiti: I know your work has been well-received in various parts of the world. Tell us about some of the awards you have garnered.

Myriam Chancy: My work has garnered a shortlisting for Best First Book, Canada/Caribbean region category, of the Commonwealth Prize in 2004 for my first novel, Spirit of Haiti (London: Mango Publications, 2003); I published a second novel, The Scorpion’s Claw (Peepal Tree Press 2005) to critical praise; and my third novel, The Loneliness of Angels (Peepal Tree Press 2010), longlisted for the 2011 OCM Bocas Prize in Caribbean Literature and shortlisted in its fiction category, was awarded the inaugural Guyana Prize in Literature Caribbean Award for Best Fiction 2010 by the trustees of the Guyana Prize, University of Guyana, Georgetown, Guyana, on Sept. 1, 2011 [Caribbean Award Jury: Stewart Brown, Funso Aiyejina, and Rawle Gibbons]. All three of my novels are currently taught at universities and colleges in the US, Canada and the Caribbean and can apparently be found in 4 out of 7 libraries across Canada.

VoicesfromHaiti: Was there one particular award of which you were most proud?

Myriam Chancy: Probably the Guyana Prize. I received that award from the hands of the President of Guyana in September 2011 in what was a regal-like ceremony. It was lovely to be honored in the Caribbean by esteemed peers.

VFH: Given all the work you have done, do you think you are due a long vacation? Where do you draw inspiration to keep going and going?

MC: I am inspired by anonymous young people and women whom I may never meet. I hope that my work inspires them to pursue their own paths. When I was still a graduate student, I gave myself the task of writing down and publishing whatever I learned and I continue to do so in both my creative and critical work. I hope they will do the same. Their stories are worth telling. Documenting.

MC: I am inspired by anonymous young people and women whom I may never meet. I hope that my work inspires them to pursue their own paths. When I was still a graduate student, I gave myself the task of writing down and publishing whatever I learned and I continue to do so in both my creative and critical work. I hope they will do the same. Their stories are worth telling. Documenting.

For those interested, I have a new (academic) book called: From Sugar to Revolution: Women’s Voices from Haiti, Cuba, and the Dominican Republic— with Wilfrid Laurier UP out of Canada; it contains full-length interviews with Haitian writer, Edwidge Danticat, Dominican writer, Loida Maritza Perez, and Cuban artist, Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons.

VoicesFromHaiti: Where were you born? Tell us about your childhood home.

Myriam Chancy: I was born in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, into a large family. My parents had met in Paris, had a first child there, and then moved back to Haiti while also working out possible opportunities in Canada. I had more than one childhood home. I lived in an Aunt and Uncle’s house, my grandparent’s house, as well as in homes in Québec City. We went back and forth between Haiti and Canada.

VFH: Memories are associated with particular settings. Are the strongest memories framed within Haiti or Canada.

MC: My childhood memories of Haiti are the strongest, probably because this was a time when most of my family still lived in Haiti. My cousins were in their early twenties, about to leave for their own futures elsewhere, though a number of them returned to Haiti to live after studying abroad.

What I remember most are my grandmother’s and Aunt’s kitchens and the feeling of safety in my childhood homes in Haiti, despite the political instability that resided outside our doors (I was born a the beginning of the second Duvalier regime in 1970). Family members nutured my independent spirit.

VFH: Who among family members holds a prominent spot in your memory?

MC: My great-grandmother. I saw her last at the age of eight. She had a large quenêpier in her front yard. I remember her teaching me how to pick and eat them. To this day, quenêpes are my favorite fruit. She was over one hundred and four when she died a few years after that last meeting. She made the best douces, but we no longer have the recipe. She also spoke a register of Kreyol that I have never heard since and wish we had had the forethought to record her since she probably remembered so many things of her life going back to the late 1800s and so many things have changed since she passed away. An archive surely died with her.

VFH: Where were you when you heard about the earthquake in 2010?

MC: I was teaching a graduate seminar but had had an eerie feeling all day checking with friends and family large and wide to figure out if anyone was in distress. It was also my father’s 75th birthday. As I went into my class, a friend told me to get onto the internet to check breaking news on Al Jazeera, that something had happened in Haiti. I learned of the earthquake about a half hour after it occurred, when my class had a break. I went on teaching and then started the interminable days of trying to track down family, friends, colleagues; though in most cases, myself and friends found who were looking for alive, every trail of contacts turned up so many dead that it was heartbreaking work. For instance, in trying to find the student of a friend and colleague who had been readying to leave for Puerto Rico for his studies, we ultimately found him and his family alive but all of the contacts we had to track him down, mostly professors at the L’Université de L’état were dead. Then came the task of having to relate that those contacts had perished.

MC: I was teaching a graduate seminar but had had an eerie feeling all day checking with friends and family large and wide to figure out if anyone was in distress. It was also my father’s 75th birthday. As I went into my class, a friend told me to get onto the internet to check breaking news on Al Jazeera, that something had happened in Haiti. I learned of the earthquake about a half hour after it occurred, when my class had a break. I went on teaching and then started the interminable days of trying to track down family, friends, colleagues; though in most cases, myself and friends found who were looking for alive, every trail of contacts turned up so many dead that it was heartbreaking work. For instance, in trying to find the student of a friend and colleague who had been readying to leave for Puerto Rico for his studies, we ultimately found him and his family alive but all of the contacts we had to track him down, mostly professors at the L’Université de L’état were dead. Then came the task of having to relate that those contacts had perished.

Most paths were like that so that every search was filled with dread and it was inevitable to be confronted with death even when survivors were found. We couldn’t find anyone for days. It was a very difficult time; I think I didn’t leave the apartment I was then living in for a full week. I’ve written a piece about those first days and weeks which readers can find at: www.vandaljournal.com<http://www.vandaljournal.com/>.

On the first anniversary of the quake, a dear uncle we’d had difficulty locating a year prior called to wish us a happy new year and talked about all he was doing for the reconstruction with optimism. I marvelled at how a year can change things. On the second anniversary of the quake, things shifted even further as aunts, uncles, and cousins, called my father to wish him a happy birthday and we could rejoice in all that remained.

VFH: What role do you see yourself playing inHaiti’s Reconstruction?

MC: The role I have been playing is that of networker and information gatherer. A great deal of my work as an intellectual has been focused on critiquing the discourse around the reconstruction which renders Haiti again a victim of neo-colonialism.

MC: The role I have been playing is that of networker and information gatherer. A great deal of my work as an intellectual has been focused on critiquing the discourse around the reconstruction which renders Haiti again a victim of neo-colonialism.

I have been focusing both on the dehistoricizing of Haiti and the place Haiti plays ideologically in the hemisphere, and now in global affairs, as reconstruction efforts continue to be crippled by foreign “investments” and lack of coordination.

I’m also very concerned with human insecurity, especially as it pertains to women and children, in the IDP camps, and more largely in Haitian society. I see my role as one of critic and supporter to assist Haitians in Haiti, across class divides and interests, in the process of fulfilling their visions for a new Haiti.

I think it is important that intellectuals not take the place of voices coming from Haiti but that we seek to understand what is going on on the ground, what the issue are, and how we can best support Haitians in Haiti.

Though Haitians outside of Haiti can do a lot of good for Haiti, I think it’s important to lend our support rather than try to make Haiti our own post-earthquake; we owe it to the thousands who perished and to the thousands still struggling, who, even prior to the earthquake, had little support.

I have to say, though, that having gone back in August, it was clear to me that Haitians who have never left Haiti are working diligently to create a new Haiti with so much enthusiasm and dedication despite losses and trauma; the energy and optimism I found from Port-au-Prince to Léogane to LaGonav was remarkable and I will do everything I can to support those efforts.

I am also involved in raising funds when and where I can. For example, I have dedicated the royalties of my last two novels to Haitian reconstruction for the last two years.

Currently, I have nominated one women’s grassroots project for a partnering project with the Fetzer foundation which is just getting off the ground ;and I am working with others on oral narrative projects. I try my best to circulate information about viable NGOs, large and small, and have listed a number on my website

VFH: It seems to me you need to keep your battery fully charged to do all that you do daily. A woman’s gotta eat! So, can we ta lk food for a moment? What does Myriam Chancy like to eat? Do you find time to cook?

VFH: It seems to me you need to keep your battery fully charged to do all that you do daily. A woman’s gotta eat! So, can we ta lk food for a moment? What does Myriam Chancy like to eat? Do you find time to cook?

MC: I enjoy cooking a great deal. I learned to cook when I found myself at my first US job as a professor in a city where it seemed like there was nothing to eat but fried foods! I’m an eclectic cook, though, cooking Caribbean, Italian, Thai, Japanese, French and made up dishes.

VFH: What is your favorite Haitian dish?

MC: Rice with pwa en sauce (kidney bean sauce), sweet plaintain (boiled, not fried), and grio – all together – and soup giromon.

VoicesfromHaiti: There’s nothing like street-side food in Haiti–for me. Have you eaten a plate of food from a machann?

VoicesfromHaiti: There’s nothing like street-side food in Haiti–for me. Have you eaten a plate of food from a machann?

Myriam Chancy: Probably, but it’s been a long time. I think the last thing I remember having are tablet or pistach.

VFH: Well, Myriam, a gwo thank you for adding your voice to our chorus. I am grateful for that. What are you most grateful for in your life?

MC: The gift of time to do my work and to discover what my work is. I am grateful for the ability to travel and discover new things. More than anything, however, I am grateful for my parents.